The morning sky was a dull grey, with low-hanging clouds over the battleship where the war that had begun more than a thousand days previously with the attack on Pearl Harbor concluded with Japan’s formal surrender on September 2, 1945. On the U.S.S. Missouri’s teak deck, the highest army commanders of the successful Allies stood in appointed positions beside representatives of the vanquished Japanese Empire. There were several white-capped sailors admiring the view below on every level and the catwalk of the superstructure towering high above.

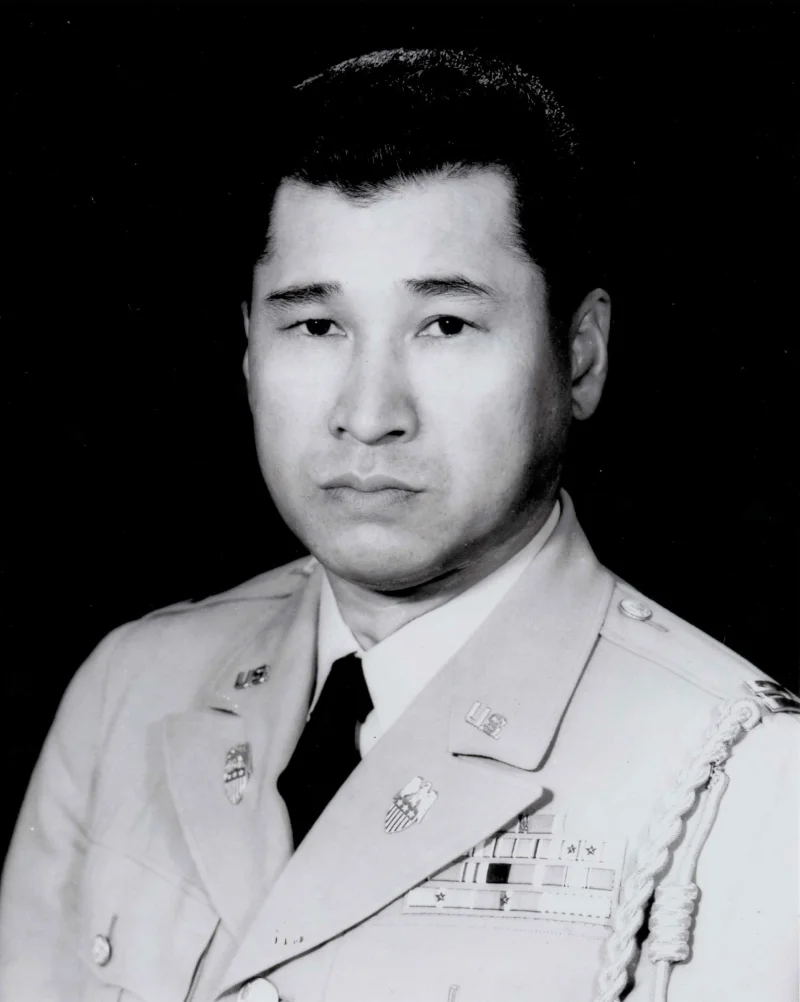

Thomas Sakamoto, 27, a tall Japanese American who was one of the Army’s newest second lieutenants in the Pacific, watched the event with a group of American press reporters while they were seated nearby on a sub deck. Sakamoto served as their official interpreter.

General Douglas MacArthur approached the group of microphones when he emerged from the ship’s stateroom and walked stiffly while reading a brief remark. The representatives of Japan and the Allies were then asked to sign the surrender document.

When Sakamoto discovered he was one of just three Japanese American sailors onboard Missouri that morning, he was even more grateful to have been a part of such history. His immigrant parents who had moved to California had sent him to a boarding high school in Japan a decade earlier so that he might learn about their native country. While he was a proud member of his family, he did not attempt to assimilate into Japanese society while he was there. He had no conflicted allegiances. His background was Japanese, yet he was an American by birth and upbringing. For the Military Intelligence Service of the United States Army, Tom Sakamoto and hundreds of other Japanese American troops had become vital assets in the battle against Japan as a result of all of the above.

Sakamoto reported with 57 other Japanese American recruits and draftees to a brand-new Army language school in San Francisco a month before Pearl Harbor in 1941, beginning the route that would eventually lead him to Missouri that morning. They were all proficient in the Japanese language and had all attended school there for at least a few years. As tensions between the two nations grew that summer, a small group of military intelligence officers who had been stationed in Japan in the 1930s warned Washington that a war with Japan would be extremely difficult to conduct due to language barriers. Few Europeans, they said, were fluent in the difficult Japanese language. Six months later, the first graduating class and the war with Japan were in full swing.

The majority of the graduates went right to the Pacific, becoming some of the first Nisei troops to participate in World War II combat. The Army kept the top ten students, including Sakamoto, to instruct at the Minnesota-based Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS), which has grown significantly. A year later, Sakamoto was sent to lead a Nisei team of 10 for the 1st Cavalry Division’s assault of the Admiralty Islands in the Pacific. While there, they translated a cache of Japanese documents that revealed vital information about an enemy attack that was repulsed, sparing American lives.

Six thousand Japanese-speaking interpreters, translators, and interrogators had graduated from MISLS by the conclusion of the war. They provided service all around the Pacific in New Guinea’s tropical rain forests and Iwo Jima’s bloodied beaches. The sweltering Burmese highlands are home to the legendary Merrill’s Marauders. the Okinawa caverns. These young men, who were almost a hidden weapon in the fight against Japan, yearned for an opportunity to prove their allegiance to the United States despite the bigotry and xenophobia that the Pearl Harbor assault had stoked as well as the removal of their families and incarceration in camps. In reality, they were engaged in two wars at once: one against the country of their ancestors and the other against racial discrimination in their own country.

However, even now, very little is known about the tale of their service. While the exploits of the all-Nisei infantry groups battling the Germans in North Africa and Europe earned worldwide acclaim during and after the war and were depicted in innumerable books and films, the existence of Nisei teams in U.S. combat forces fighting in the Pacific was one of the best-kept secrets of the conflict. These teams could understand the Japanese, read their messages, and interrogate POWs. After then, military intelligence issues remained shrouded in secrecy, and even after World War II documents began to be disclosed decades later, most of their narrative remained unaltered in archives. Surprisingly, the Army never created a list of Japanese Americans who served in the Pacific.

Japanese Americans, who had ancestors from a country with which the United States was at war and were mistrusted by many of their fellow citizens, as a result, turned out to be enormous assets for the U.S. military because they were highly motivated to defeat the enemy and knew them better than anyone. Their timeless message of courage and patriotism should not be overlooked in a country like America where prejudices against people are all too common based on color, ethnicity, and country of origin.